Happy new year, friends! If you’re reading this, you’re an intellectual, you know damn well January 1st is no more significant than another twenty four hours in our submission to a capitalist system spiked with rapid technological advancement and an utter disregard for humanity and the planet at large, but what better time to learn to play piano?

I don’t want to convince you to practice an instrument — if you don’t already — I need to convince myself to practice an instrument, more specifically, the sale-price Yamaha I bought a few months into the pandemic (eventually driven from New Jersey to Tucson, only to gather dust and disappointment on the face of Ben Folds, who silently judges me from the face of The Best Imitation of [Himself] sitting on the music stand).

I suspect a lot of sad souls have this kind of depressing relationship with a musical instrument. You know it would feel good, you know you would it enjoy it, but it’s too late, and how are you going to get started now? I’m turning 35 next month, and that’s considered too old for a lot of things more ancient than humanity’s relationship with musical instruments. There’s also a guitar haunting my musical sense of identity. It was a birthday present from my parents that swept me off my feet in a state of no direction. Driven mad with the urge of fresh passion, I wrote ten songs in a month… then put it down and failed to pick it back up again, creating a chaotic swarm guilt, shame, and laziness in the form of anxious avoidance. Sometimes I look over at the sad, white wall where the Lucero leans, sighing, “Someday…” like an old lover is trapped in a pleather case in the corner of my office.

As part of a strange practical joke that I’ve been playing on myself, I spent two years studying the way music education can change our brains, enhancing our ability to communicate and evolve as a species… but I never picked up an instrument. The Yamaha and the Lucero sat gathering dust. In my research, I traveled to the Museum of Music Education in Phoenix, Arizona, where I met a religiously-dedicated volunteer, who led tours of the hallowed halls in her spare time. Indeed, she said she loved nothing more than to be there in the presence all those instruments from all over the globe, but she had decided it was too late for her to play the flute again, and, I swear, she wasn’t kidding. I can’t blame her.

My journey into researching music education got tangled up in heartbreak. I was writing the book for a musician and composer (who was not Yo-Yo Ma, though I wish) with a promised forward from one of the world’s post powerful spiritual influencers (who, unfortunately, was someone other than Oprah). The book was a memoir-based self-help book about the power of practicing an instrument, and I dove in headfirst, discovering a convincing case that music is a human right — an argument intended to bolster legislation on the power of music education. I don’t want to say this administration killed any hope of the dream, but it certainly didn’t help.

The subject of music education is fascinating. Everyone lights up about music. It seems like we all share this inherent, perhaps even biological predisposition to know the power of music education, most of all the music teachers, most of which have to pitch for their programs year after year, like paupers clicking for help with a PowerPoint. We all “know” the power of music education like it’s common sense, and, yet we are not making sure that each and every kid has an instrument in their hand before Kindergarten. This is an access issue and a cultural issue, there are rich children paying upwards of college tuition to go to private school without a music program. What would it take to convince humanity to shift the future of the next generation? On the cheap, $250 per kid, and that buys them access to an instrument that can fine-tune their brain for the entirety of their lifespan.

The science of brain plasticity itself is young. The MRIs, Pet Scans, and EEGs that revealed the effect of practicing an instrument on the brain began really got cooking in the ‘90s. We are just now learning about brain plasticity, the way the brain is constantly learning from our experiences of the world around us. In all of the research I read over two years, interviews with academics, teachers, and musicians, the most exciting fact in making the case for music education is easily this: Did you know we all hear the world differently? That blew my mind.

It turns out our hearing is a like a pair of sneakers. If two very different people with very different lives wore the same pair of sneakers, the soles would look different in about a week, certainly in a month, or a year, or longer. The way those two people hear the same environment is different, especially if they have learned a language, played a sport, or practiced an instrument. In her book Of Sound Mind: How Our Brain Constructs A Meaningful Sonic World, Dr. Nina Kraus says our hearing is as unique as our fingertips, but also dynamic. She emphasizes that we do not truly appreciate our hearing, how essential that sense is to way we connect to ourselves and each other. If we can’t all politically insist that music is a human right, we can at least agree that all this noise is bullshit.

The way we hear is the difference between sound and noise, a distinction based on which sounds we learn have meaning to our lives. One of Dr. Kraus’s earliest breakthroughs was training rabbits to perk up to trumpets. It was Pavlov plus modern technology, monitoring the changed firing of neural synapses once the sound of the trumpets found meaning with the help of a carrot. Dr. Kraus has built her MIT Lab, Brain Volts, around the seed of that finding, the understanding that our brains change based on which sounds we learn have meaning.

Playing a musical instrument is one of the most effective ways to tune your sound mind, and the magic number there is two years. That’s how long it takes to see lasting change. Brainvolts was able to scan the brains of students practicing instruments in schools in Chicago and LA. One year into hauling lab equipment into trailers and custodial closets, they came up empty-handed, but pushed forward. Two years later, they tested again, and found that the students had changed their neural signatures through practice.

For kids at school, that means enhancing their ability to learn how to read, or even just hear what their teacher is saying. When they get older, it wards off dementia and Alzheimers, even if they never practice again after high school. For every single person alive on this withering planet ruled by technocrats, it can help inoculate the damage we have done to our nervous systems by being in the constant state of alarm that is hearing noise as sound when rings out from our phones and demands our attention. And so, in a small effort to resist the robots plowing and harvesting our energy for profit, you might like to spend 10 minutes a day playing an instrument. If you practice an instrument for at least 10 minutes a day, you will permanently change the way you hear the world around you, enhancing your ability to tune into the reality of what happens IRL. The more you practice, the more benefits you will see, but to get started I’m going for the bare minimum. January 1st, 2026, and I am committing to practicing the piano and guitar for at least 10 minutes a day. I’ll write to you here every week, and see if it feels any less insane.

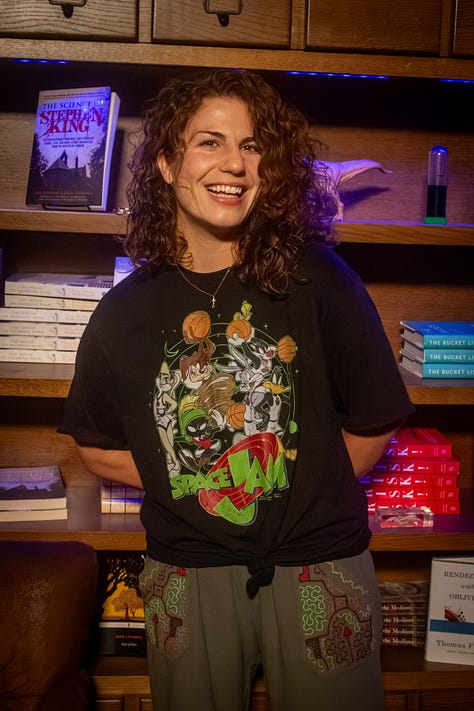

Lauren Duca is an award-winning and losing writer who was profiled in The New York Times and canceled by Buzzfeed before she ran off to the mountains to join a cult. After two years of sitting with ayahuasca like that was a career path, she has no choice but to pursue comedy. Pancake Brain is a (free) Friday newsletter documenting two years of trying to get back online while learning how to play music.